Effective Refactoring, Part 3

The Imperative Role of Tests

February 2, 2018

This is the third part of a four part series on effective refactoring.

- Part 1: Asking the Right Questions

- Part 2: Formulating a Plan

- Part 3: The Imperative Role of Tests

- Part 4: Rewriting the Code

If you don't like testing your product, most likely your customers won't like to test it either.

Read any book or article on software testing and most of them will mention, at some point, that developers aren't crazy about writing tests. I'm not going to debate the accuracy of that statement, but I am reminded of a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson:

Your actions speak so loudly, I can not hear what you are saying.

If you write tests and appreciate their worth, your application will have a lot of tests, plain and simple. If the goal of your refactoring project is to fail spectacularly, don't write any tests.

Tests will alleviate one of the main stressors of refactoring: the possibility of breaking the application. Let's face it, no developer is perfect and no tool is completely error proof. Throughout the course of rewriting code, you may accidentally delete a line or purposefully remove some logic that seemed unnecessary. If you're making a significant amount of changes to a file, these breaking changes might go unnoticed. Tests will always notice.

In Part 3 of this series, I will walk you through the process of setting up an effective testing infrastructure. I'm using Jest and Enzyme because getting up and running is relatively quick. I recommend reading the following articles for configuring these libraries in a React/Redux app.

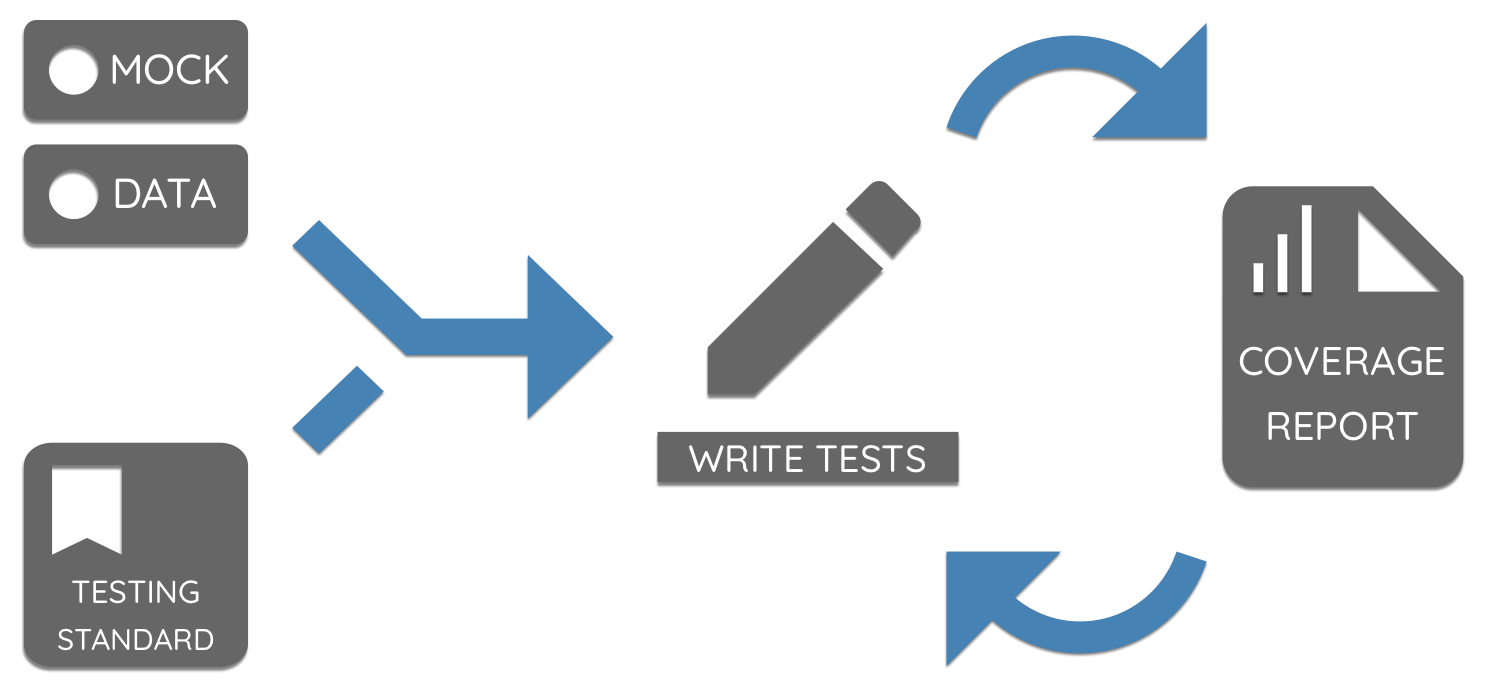

For the purposes of this article, I don't want to dive too deep into the setup and configuration. One of the first steps to building a solid testing foundation is setting up a source of reliable mock data. Let's get started!

Setting Up Mock Data

If you're working with an existing application, you have the advantage of knowing the shape of existing data and how it's used. In most cases, the API is refined and may only require minor tweaks as new features are being added. For the application I refactored, I created two files with data: one with the API responses and one with a populated Redux state. It may take a little legwork and a lot of copying and pasting to create these files, but it only needs to be done once.

Having these data files serves two important purposes. The first and obvious one is that many of the elements you'll be testing will display or manipulate data in some way. The second is the ability to quickly reference the shape of the data to determine the most effective tests to write and why they may be failing.

Storing the state and API responses may not always be feasible if the data is sensitive. If that's

the case you can use a library like json-schema-faker

with faker or chance to

generate random data. These libraries allow you to use a seed to generate the same data repeatedly, but

I'd recommend that you generate the data once and save the generated data in the repo, rather than

use a seed to generate data every time you run your tests.

I stored my files in a __fixtures__ directory next to my Redux files (actions, reducers,

selectors). The folder structure looks like this:

/src

/components

/constants

/containers

/redux

/__fixtures__ <--- This directory contains fixture files

/state.js

/responses.js

/app

/appActions.js

/appReducer.js

/appSelectors.js

/...

The easiest way to get the entire shape of the Redux state is to use the

Redux DevTools extension,

select the Raw tab from the state view, copy everything, and paste it in a JavaScript file

with a module.exports statement. I would advise only taking a small chunk of the records from

state and API responses to reduce the size of the Jest snapshots. Use you best judgement when

determining how many records you feel is suitable to retain. If one of the API responses returns

an array of 400 records, you could definitely eliminate a significant percentage of those and still

write effective tests.

Having valid data is imperative to preventing regression errors. If the data isn't representative of what the application consumes, no amount of tests will ensure the success of the refactor.

Now that you have the data ready to go, it's time to move onto the next step: establishing a standard format and style guide for tests.

Standardizing Your Tests

You'll end up writing a great deal of tests over the course of a refactoring project. When I first

started writing tests, I was relatively new to testing in general. My tests were disjointed, the

wording was different between files, and the structure of the tests with regard to describe

blocks varied even when testing two very similar components.

I've found that establishing a testing standard made writing them much easier by reducing cognitive load needed to ensure I was writing quality tests. The presence of, and adherence to, a standard is more important than the minute details. You're free to put together something that works best for you, but there a few guidelines you should follow.

Determine Where Test Files Will Go

Some people prefer to mirror the src/ directory and place their test files there. Maybe you

prefer to name your test files with a .spec.js extension, while others prefer .test.js.

Regardless of what you choose, be consistent. The default Jest configuration

specifies that you co-locate your tests in a __tests__ directory and use .test.js for the file extension, so that's the

route I chose. Once you decide on a standard, add it to the README so anyone else working on the

app in the future will follow suit.

Establish a Format

You should establish a format/structure for each context being tested (i.e. React components, Redux

selectors, etc.). For example, every React component and container test file I created has

a setup function at the top of the file that looks like this:

const setup = (propOverrides, renderFn = shallow) => {

const props = {

propA: 'Some Value',

propB: false,

onClick: jest.fn(),

...propOverrides,

};

const wrapper = renderFn(<AppComponent {...props} />);

return { props, wrapper };

};

This made it much easier to test my components without having to write a lot of extra boilerplate.

I also set up a specific describe block structure for React components.

describe('Component A', () => {

describe('Snapshot validation', () => {

it('matches its snapshot with valid props', () => {

const { wrapper } = setup();

expect(wrapper).toMatchSnapshot();

});

});

describe('Event validation', () => {

it('fires props.onClick when button is clicked', () => {

const { wrapper, props } = setup();

wrapper.find('button').simulate('click');

expect(props.onClick).toHaveBeenCalled();

});

});

// Note: This is only for connected components.

describe('Redux validation', () => {

const store = {

getState: () => state,

dispatch: jest.fn(),

subscribe: () => {},

};

it('renders when connected to Redux state', () => {

const wrapper = shallow(<ComponentA store={store} />);

expect(wrapper).toHaveLength(1);

});

});

});

I do something similar with Redux actions, reducers, and selectors. I use WebStorm's File Templates feature to quickly create the test files depending on what I'm testing. Your editor most likely supports snippets or file templates, so I would advise creating templates to ensure you adhere to the standard. It helps to include a brief overview of this in the README file for posterity.

Writing Tests

Now it's time to get down to brass tacks. If you're not familiar with writing tests, it can be daunting to figure out the best course of action. You might be asking yourself a lot of questions:

- Where do I start?

- What should I be testing?

- How will I know if I've written enough tests to prevent bugs?

There's no definitive “right” answer to these questions, but the methodology I followed throughout the course of my project produced successful results.

Where Do I Start?

In Part 2 of this series, I stressed the importance of having a plan. If you put together a course

of action, determining where to start writing tests should be simple. Let's say you're starting

on a task to refactor the Redux actions, reducer, and selectors for the UI state. You've got the

state data ready to go, so writing tests should be relatively straightforward. You'll need a

library like redux-mock-store to mock out the state to test actions.

I lean pretty heavily on snapshots for testing the reducers and selectors, even if a selector only returns a

string or boolean value.

Make sure you write all the tests before you change any code. Some of your tests will probably fail after you've refactored the code. The failed test will indicate if the failure was due to a deliberate change or an accidental one. Snapshots are invaluable in this regard. It's easy to miss a field or misspell an object key, and seeing this in the diff will make rectifying the issue trivial.

Only write tests for the parts of the code you're refactoring and any code directly affected by the changes. Trying to write tests for the entire application before starting the refactor will lead to burnout and frustration. Chasing down the dependencies and writing tests to cover all your bases can be frustrating, but will give you valuable insight into the codebase and present additional opportunities for refactoring. Add or update your project to reflect these opportunities, otherwise you could forget them and follow the wrong path.

What Should I Test?

When you're just getting started, the easiest and relatively reliable way to determine what to test is code coverage. Jest has code coverage built in, and you can generate an HTML report with the coverage percentage and what parts of the code aren't currently being covered by tests. Line coverage makes you feel good about yourself, but branch coverage is what you'll want to focus on. If you want a detailed explanation of the difference between coverage types, check out this article by Jason Rudolph. I'll talk about why code coverage isn't the single source of truth in the next section, but it's a great tool to get you on the right track and keep you motivated.

How Will I Know When I've Done Enough?

This one is a little trickier to answer. When I was first getting started, I used Jest's code

coverage as gospel. As time went on and my experience grew, I found that this isn't necessarily

the best course of action. Coverage is an excellent tool for evaluating which sections of your

code are (or are not) being tested. If you have an if statement in a function, and the else

condition isn't being covered by a test, the coverage report will point that out. It's nice to

see a high percentage and a lot of green on the report or in the terminal, but just writing

tests to get into the green won't prevent bugs.

The articles and books that have been written about writing good tests are numerous and opinionated. I like to look through a function a few times to make sure I understand the logic, then write tests that deliberately try to break it. What if a field is missing from an API response? What happens if the response is null?

For example, let's say there's a selector that sums up the budget allocated for each salesman in

a specific district. The sales manager that runs that district has a total available budget. The

total available budget should always be higher than the total allocated budget. What happens

when it's not? Is there an if statement that covers that? Reading the code and writing the

tests will often make you think of situations like that. Code coverage is just going to tell

you that the function is covered.

Wrap Up

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I'd like to reiterate how important tests are to successfully refactoring a codebase without breaking existing functionality. Some things are going to fall through the cracks, but a leaky faucet is much easier (and cheaper) to fix than a burst pipe.

If you start with reliable mock data, a good standard, and write the tests alongside the code you're refactoring, the process should go relatively smoothly. There are many challenges you will encounter in a rewrite, but a good test suite will instill the confidence needed to overcome them.

If you've got a good testing framework setup, and you wrote tests for the code you're refactoring, it's finally time to start changing the code! In the final part of the series, I cover tip, tricks, and some pitfalls that go along with a rewrite.